The RBI, on its part, has been constantly flagging the risk from continued high rate of inflation.

Much before data released on November 29 showed that India’s economic growth had slumped to a seven-quarter low of 5.4 per cent in July-September, discussions within the government had questioned RBI’s upward revision of growth estimates to 7.2 per cent for 2024-25 and flagged worries about the cumulative impact of its prudential measures, The Indian Express has learnt.

There were apprehensions that these had begun hurting India’s growth prospects and the RBI’s decision to keep policy rates static because of food and gold/silver inflation, has made the effective real rate of interest for the non-food part of the economy very high now, top officials said.

The RBI would not agree with this assessment, said some analysts and experts tracking the central bank’s regulatory and monetary policy actions. They said housing loans are at 8.5 per cent, MSME loans are at 10-11 per cent, and if you net out inflation at 6 per cent, then the rates are not so high.

A government official said, the first red flag came when RBI raised the GDP growth forecast for 2024-25 to 7.2 per cent in June from 7 per cent in April since it was out of sync with other signals. “At this point, incremental information – very hot summer, monsoon getting delayed – was negative,” the official said.

This move by the RBI surprised many in the government. While there were expectations that the central bank would become more cautious, it became more confident about the growth number. On top of this, the RBI also kept its key policy rate unchanged at 6.5 per cent since February 2023, which had by the beginning of the second quarter resulted in high lending rates for non-agricultural sectors.

But analysts tracking the central bank said the upward growth revision came in the backdrop of a very strong momentum from Q3 and Q4 in 2023-24. “Growth slowed in the first quarter this year because of low capex in the Centre and states, and there is a blip in Q2 mainly because of excess rains in August and September when construction activity was disrupted, and mining and electricity also slowed down,” one such analyst said.

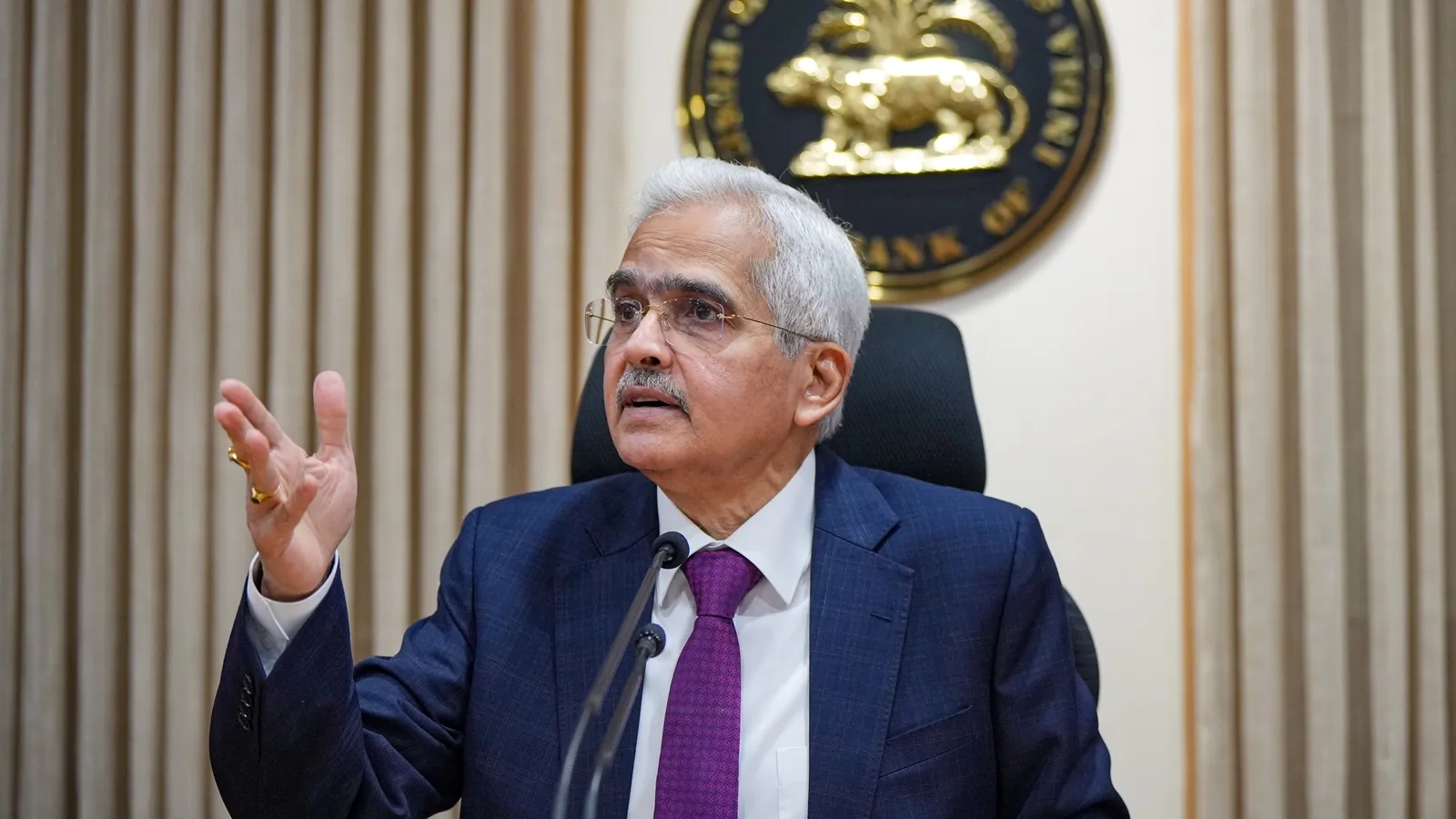

All eyes are now on RBI’s monetary review meeting December 4-6 – with Governor Shaktikanta Das’s term expected to end December 10.

Government officials said the central bank’s many credit actions and macro-prudential measures such as higher risk weights on unsecured personal loans, a discussion paper on higher provisioning for project loans, and steps for digital lending were seen to be all well-intended and individually correct at the respective points of time. “But their cumulative impact was denting growth prospects,” the official said.

The government thinks these measures were important, singed as it is from what it feels were the “mistakes” in the past that led to the cropping up of doubtful and bad loans.

But the government couldn’t still come to terms with what it feels is RBI’s misplaced alarm over high credit-deposit ratio, which eventually has led to a sharp moderation in credit growth. The credit growth rate dropped to around 11 per cent from over 16 per cent in January this year. “Their (RBI’s) insistence on bringing down the credit-deposit ratio – if you bring down credit growth, you bring down deposit growth. You ask any banker, you give credit, and then it creates deposits. But if you crimp credit growth, you’re going to crimp deposit growth as well,” the official explained.

The RBI’s financial stability report, published in June 2024, says the credit-deposit ratio meanders for 41 months before it comes back, the official pointed out. “So, it is not as if the episode of the credit-deposit ratio growing above the trend is happening for the first time. It comes down over time, with the credit growth slowing down. Collectively, they may have exerted an influence,” the official said.

Analysts tracking the banking regulator attributed the prudential actions to credit exuberance – credit card outstanding was growing at 30 per cent, unsecured loans at 30 per cent, and NBFCs were diluting credit appraisal norms and underwriting standards. Credit was being pushed irrespective of demand, and the RBI saw clear signs of a future crisis. The RBI actions in November slowed down credit growth in those segments, and this was the desired objective, they said. When a bubble bursts, then all questions are asked to the regulator, the analysts said.

As the RBI maintained its guard against the high rate of inflation over the year, concerns also emerged within the government on whether the monetary policy stance is becoming too tight. It was felt the central bank was focusing a lot on food inflation, which is not completely in its control, and has been rising primarily due to price shocks in just a few items such as tomato, onion, potato among other perishables.

The RBI’s action against inflation, especially as a supply-side driven issue in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, was seen as ideal but the grip does not seem to have been loosened on time as per government officials.

“By reacting to food inflation, where they have no control, where there are no second-round effects, and even core inflation is more influenced by gold and silver rather than overall, it is very clear that your effective real rate of interest for the non-food part of the economy is very high now. So effectively, there is a restrictive monetary policy,” the official said.

Retail inflation rate surged to a 14-month high of 6.21 per cent in October with a sharp rise in prices of food items, especially fruits, vegetables, meat and fish, and oils and fats.

Food inflation shot up to a double-digit level of 10.87 per cent in October — a 15-month high — from 9.24 per cent in September, and 6.61 per cent in the year-ago period. Food and beverages account for 45.86 per cent of the total weight of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), on which retail inflation is based.

Barring two months of July and August this year, the headline retail inflation rate has remained above the 4 per cent mark in the 4+/- 2 per cent band of RBI’s medium-term inflation target for 59 months.

The RBI, on its part, has been constantly flagging the risk from continued high rate of inflation. In the October Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das had said the RBI cannot risk ‘another bout of inflation’ and so there is a need to wait for more evidence of inflation aligning durably with the 4 per cent target. If bank interest rates are low when inflation is high, it would mean a further credit exuberance, and lead to dilution of the quality of balance sheet of banks, said analysts explaining RBI action.

The RBI Act, analysts pointed out, mandates price stability, and is defined in terms of headline inflation i.e., 4 per cent +/- 2 per cent. Whether it is food that causes inflation to rise, or some other constituent, at the end of the day, the mandate is to ensure it does not breach the upper end of the band, i.e., 6 per cent, they said.

“In developed countries, when you have inflation targeting, you are effectively targeting labour income. Central banks react when wages start rising. In a developing country, given food is a larger component, the moment you start reacting to food, you are reacting to farmers’ terms of trade. Effectively, it is not a technocratic decision; it is a political economy decision,” the government official said.

The sole focus on inflation targeting has come under question after the recent growth fallout in Q2, bringing the spotlight on the inflation versus growth debate and whether the country is facing a cyclical slowdown and is in need of anti-cyclical policy measures.

“If there is a second-round effect, you must react. If it becomes generalised, you must react. My point is that the core inflation (non-food, non-fuel inflation) has suddenly gone up in the last three months from 3.2 per cent to 4.2 per cent…you take out gold and silver, core inflation is tame. So, you cannot say that food inflation is passing the second round of the passthrough effect on gold and silver. That’s a bit far-fetched,” the official said.

Leave a Reply